From Single drop-down to Multiple check-boxes

TL;DR: Follow the incremental approach below. Divide the entire problem into small sub-problems and deploy them one by one:

- define the new DB structure

- fill it in along with the old DB structure simultaneously

- migrate the old data to the new one

- define the new associations and make the code use them

- drop the old DB structure and the code that’s not relevant anymore.

In this article you will:

- learn how to maintain a Rails application in production with zero downtime

- see how to make necessary changes on the current DB structure and deliver new features

- figure out how to ship new features to production without outages, bugs, and downtimes

- feel what’s Continuous Delivery by a case that happened with a Rails application in production.

Problem

Picture a Rails application that’s deployed to production. And it serves requests from real users all around the clock. That is, a live Rails application performs 24/7 for now and forever. Maintenance downtime is not desired and must be avoided as much as possible. This is the most important requirement a good business asks about, isn’t it?

As time goes by, the business decides to make the following changes. There is a drop-down allows picking one choice on UI. But from now on it should have multiple choices. Speaking in ActiveRecord terms, there is a belongs to/has many association in the system that has to be changed to has and belongs to many.

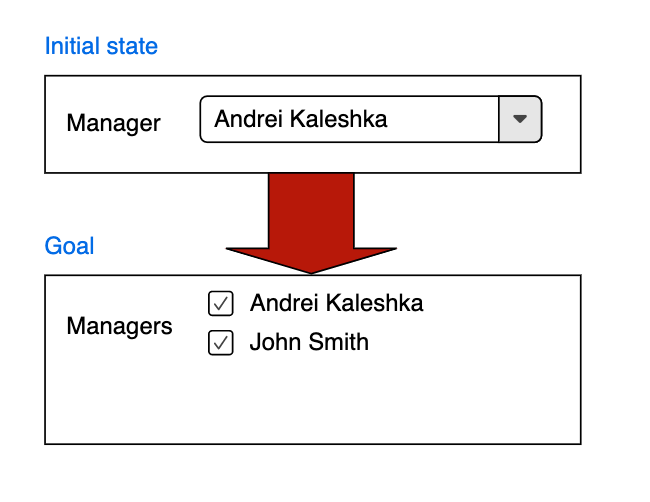

A graphical explanation of the problem:

How to approach that? Well, someone might think it’s not a big deal for MVP, PoC, or a fresh startup without real users. And that’s true. In all these cases everything can be changed and re-deployed with the old data deleted at a time.

But for a mature live application with zero downtime requirements, where any data loss or bugs are not acceptable, this exercise might be a big challenge.

This post guides step by step making the transition above happen without any outages, breaks, data loss, or bugs. And it turns out the suggested idea follows Continuous Delivery approach So that it brings clarification on what that chicky term means.

Starting point

The following example supposes to bring more clarity. It dives deep into the problem and allows to feel the describing solution. So that similar situations can benefit from the knowledge.

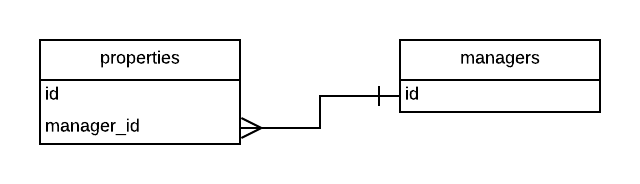

Consider a real estate system that has properties. And managers that are responsible for them, i.e. add properties into the system, keep them up to date, make them inactive/active/searchable/etc. From Rails perspective that means there are Property and Manager models. They relate to each other as Property belongs to Manager and Manager has many Property:

class Property < ApplicationRecord

belongs_to :manager

end

class Manager < ApplicationRecord

has_many :properties

end

In DB it looks like that:

Nowadays, there are many technologies to implement UI. That’s why it’s barely possible to give a common recommendation on how to handle that part of the system. For simplicity, assume that UI is rendered by the traditional Rails approach on the server-side in “views”. The following assumptions and suggestions are based on this agreement.

From the code point of view it means that somewhere there are calls:

- on model, controller, or view layer that

- read data

@property.manager,@property.manager_id,@manager.properties,@manager.property_ids - write data

@property.manager_id=,@property.manager=,@manager.property_ids=,@manager.properties= - allow params

params.require(:property).permit(:manager_id)

- read data

- on view layer that

- render HTML

= f.input :manager_id, ...,select_tag :manager_id, ...,f.input :propery_ids, ..., etc.

- render HTML

Note, the methods above can be called explicitly. It’s possible to find them by “grepping” the code easily. Or they can be called implicitly. For example, with the mass assignment of parameters to the models. But nevertheless, whenever the property-manager relation needs to be addressed, the methods above are eventually called. And that in turn means, they form an interface. An API if you will.

Goal

Our destination is the following code:

class Property < ApplicationRecord

has_and_belongs_to_many :managers

end

class Manager < ApplicationRecord

has_and_belongs_to_many :properties

end

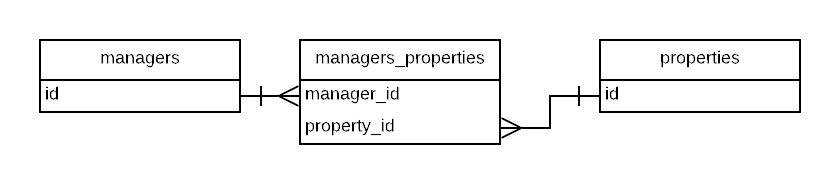

And its corresponding DB state:

If the necessary changes take place at once it means the calls @property.manager, @properly.manager_id, @properly.manager_id=, @property.manager= are no longer possible. They are replaced with the respective calls @property.managers, @properly.manager_ids, @properly.manager_ids=, @property.managers=. In other words, they break the current interface - API mentioned earlier. And these changes at once are dangerous. They may impact the system. There may be a lot of changes that have to be deployed at a time. Eventually, that may lead to unexpected bugs or even outages. No one well-established business would accept that.

What to do

For that reason, it’s better to deliver the changes gradually. That would allow shipping many small pieces to production continuously not blocking the whole development process or the entire business uses the software. That would provide immediate feedback on whether the deployed small piece works or not. A small not working piece can be fixed or rolled back much easier and faster than a huge bunch of changes. That reduces risks. It makes the delivery process comfortable and safe for both sides: working business and software development. It’s a guaranteed nerves-free process.

But first, these small self-sufficient pieces should be identified. That may seem hard and not obvious. In fact, this suspect is true. But once one feels how to do that on a particular example, like this one, similar cases should be easier to tackle.

On the very first step think about the initial and the final stages. What’s the difference between them? Which places should be changed to move from the starting point to the final one? The previous sections have already figured out that. These are places to change:

-

DB structures. A new table

managers_propertiesfor the has and belongs to many association should be created and the old columnproperties.manager_idshould be deleted. -

Data. Remember, the old column has to be represented by another one

managers_properties.manager_idin the new state of the system. So there should be a data migration fills in the new table with the old data. That allows not to lose data when the new data structure becomes actual. -

Active record API. Mind the old association

@property.managergets renamed to@property.managersalong with the bunch of automatically generated readers/writers methods. All the places that refer to these methods should be modified appropriately. -

UI. The drop-down with a single choice should be replaced with a group of check-boxes that allow many managers selection (see the first picture of this article).

Step 1: DB structure changes

My suggestion is to start with the DB structure first if this step is present in the list of required changes. In our case, it’s there.

Its implementation is not hard: just make a usual Rails migration creates the new table. It can be shipped without nerves at all.

Pay attention, as all further steps this is an easy change can hardly break something on production servers.

The only caveat is not to forget necessary indexes, foreign keys, columns with correct types, and constraints. Otherwise, a new migration should be added and deployed again. That takes time. So it’s better to spend some time on analysis of the requirements. Try to anticipate possible usages of the new structures at this stage. The spent time defines a correct DB structure is a good investment as it will save time later.

Let’s observe the following migration should satisfy all the needs:

class CreateHbtmTable < ActiveRecord::Migration[6.0]

def change

create_table :managers_properties, id: false do |t|

t.belongs_to :manager, foreign_key: true, index: false, null: false

t.belongs_to :property, foreign_key: true, index: false, null: false

end

add_index :managers_properties, [:manager_id, :property_id], unique: true

end

end

Pay attention to the table name. It should contain names of the two joined tables by the underscore, pluralized, in the lexical order. Refer to the original documentation, if there are questions.

To keep the data integrity:

- the columns

manager_idandproperty_idare not nullable - there are the foreign keys constraints for them as they refer to other tables

- there is the unique index for

manager_id + property_id.

A PostgreSQL select query uses a multicolumn index if any of the filtering fields are part of the index. In other words, the compound manager_id + property_id index will come into play for both ActiveRecord statements .where(manager_id: ...) and .where(property_id: ...). That’s why there are no separate indexes for property_id and manager_id. This not only reduces the DB structure complexity but also saves space on the data store.

Keep in mind, this trick with complex indexes may not work for some older PostgreSQL versions or other databases, such as MySQL. That’s why this question should be verified in each particular case.

Step 2: start writing into the new DB structure

The previous step migration can be deployed without any problems. But the created table is not useful while nothing writes into it. While empty, there is no point to read from it. Let’s start writing then!

We need to fill in the currently known data from the old belongs to association into the new table despite the fact it supposes to hold the new had and belongs to many association. This trick guarantees that switching to the new association doesn’t lose any data. In other words, the data represents the manager-property association should write into the old field properties.manager_id and into the new table managers_properties simultaneously.

There are at least two ways how to do that in a Rails application: use ActiveRecord callbacks or DB triggers. Which one to choose is up to the code authors. Both solutions have pros and cons. But play well if properly implemented.

Whatever way to choose, the following logic should be implemented:

- if

property#manager_idgets changed:- the

managers_propertiesrow havingproperty#idandproperty#manager_id_wasshould be deleted - the new row with

property#idandproperty#manager_idshould be inserted if the new value forproperty#manager_idis notnil

- the

- if a property gets removed, the corresponding row in

managers_propertiesshould be removed - if a manager gets removed, the corresponding association

property#managershould be nullified and the corresponding row inmanagers_propertiesshould be removed too.

If go with ActiveRecord callbacks, it may require many changes and much more effort to put. Callbacks are skipped in some cases. For example, #update_column, #update_columns, .update_all calls on ActiveRecord models don’t execute callbacks. Take into consideration that these methods can be called with meta-programming implicitly. And now the implementation doesn’t look easy at all. All the code should be read carefully. And all the places that call these and possibly other methods should take care of the simultaneous write. Additionally, if some new code is added afterward and misses that point there may be data inconsistency.

That’s why it’s better to use DB triggers. Once they are written they work as designed without any caveats. No need to read the whole codebase searching the methods above and changing those lines. No need to implement some tricky code, etc. Check out the implementation for PostgreSQL:

class AddTriggers < ActiveRecord::Migration[6.0]

def up

execute <<~SQL

create extension if not exists plpgsql;

create function update_managers_properties() returns trigger

language plpgsql

as $$

begin

if coalesce(new.manager_id, 0) != coalesce(old.manager_id, 0) then

delete from managers_properties where manager_id = old.manager_id;

if coalesce(new.manager_id, 0) != 0 then

insert into managers_properties (manager_id, property_id) values (new.manager_id, new.id);

end if;

end if;

return null;

end

$$;

create trigger align_managers_properties after insert or update on properties

for each row execute procedure update_managers_properties();

SQL

end

def down

execute("drop function update_managers_properties() cascade")

end

end

Just run this migration and from now on changes to the belongs to association will make appropriate changes in the many-to-many table automatically.

It’s supposed the models code looks like that:

class Property < ApplicationRecord

belongs_to :manager, optional: true

end

class Manager < ApplicationRecord

has_many :properties, dependent: :nullify

end

Thanks to Rails’ dependent: :nullify option above, whenever a manager gets removed it sets manager_id to null for all of the associated properties. That change to null executes the DB trigger. That in turn means, all the data integrity requirements above are satisfied.

Now it’s time to deploy this migration to production.

Step 3: migrate the old data

But that’s not all when it comes to data. There is still old data on the properties.manager_id without related managers_properties row. This can be fixed with so-called “data migration”. In short, it’s just a code snippet that makes the job done. There are many ways to implement it. All of them can be found in another article Change data in migrations like a boss.

Run the following SQL snippet against the production DB and that makes all that’s needed on this step:

insert into managers_properties (property_id, manager_id)

(select id, manager_id from properties where manager_id is not null)

on conflict do nothing;

The snippet is idempotent, so that it can be run many times without any harm to data. Also, it doesn’t conflict with any other process is writing data into managers_properties at the same time due to whatever reason.

Step 4: verify data

To prove the data is consistent, it would be good to allow the system to work for a while with the deployed steps above. Say, for one week. After that run this script against production DB:

select id, manager_id from properties where manager_id is not null

except

select property_id, manager_id from managers_properties;

select property_id, manager_id from managers_properties

except

select id, manager_id from properties where manager_id is not null;

The first select statement checks whether all filled in property-manager relations have corresponding rows in managers_properties table. It should return no results. The second one checks if there are no “aliens” in the new table. The result should be empty as well. Both statements together guarantee that the old belongs to/has many DB data structure is in sync with the new one - has and belongs to many.

Step 5: switch to has–and-belongs-to-many association

When the data integrity between the old and the new structures is proved, there is only one major step is left. This one relates to UI changes. It supposes to have fixes applied to the rest places of a Rails application: models, views, controllers. Probably, the easiest place will be model as it needs only the definition of the new relation:

class Property < ApplicationRecord

has_and_belongs_to_many :managers

end

class Manager < ApplicationRecord

has_and_belongs_to_many :properties

end

Changes to controllers may differ from project to project. But commonly the idea is to allow manager_ids instead of previous manager_id going through params. For example, if use Strong Parameters the code params.require(:property).permit(:manager_id) should be changed to params.require(:property).permit(manager_ids: []).

On the view layer, the form updates managers for properties may look like this:

= f.collection_check_boxes :manager_ids, Manager.all, :id, :id

All of these changes may be deployed at once or incrementally. For example, the views that render read-only information of the association can be delivered first. After this, controllers and models can be prepared for the new associations along with params structure without dropping the old functionality yet. Next, the UI updates property managers can be changed.

Step 6: cleanup

On the final step, the outdated code should be just dropped. It may include the following changes:

- removal of the old

properties.manager_idcolumn. Keep in mind, it should be done in several steps: first, ignore the column on the code level, then delete the column from DB. More about this is here - removal of the old defined associations along with old

paramskeys - drop the trigger along with its function

- scripts/snippets/rake tasks that refer to the old associations yet should be updated or deleted.

And that’s all steps needed to make the transition requested by the real estate business happen.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how a DB change on a Rails application with production setup should be done. This is a multi-step and not fast process. It takes time to make the transition happen without bugs and downtimes. At first glance, the given task may seem too hard. But all the required steps are small and easy.

The described technique is a very powerful tool confirmed by experience on live applications. The post shows the concrete example of how to change a single select to multiple choices on UI. But the idea applies to any transition requires changes in DB on a Rails application that has production setup with zero downtime 24/7 requirements.

Unfortunately, it’s hard or even not possible to describe all the niceties of the whole process. There are still many aspects this article doesn’t show:

- how to understand exact places in the code that require changes

- how to handle the migration if UI is a separate single page application (SPA)

- how to implement the parallel write into the old and the new DB structures if go with ActiveRecord callbacks. Is it worth at all? Partially, this question was elaborated in this article. But those brief explanations may seem not convincing enough.

If you have any of those or other questions, don’t hesitate to ask me. Thanks for your attention and happy bugless coding in production!